Cristina Jakob

The present work was elaborated and first presented in the course “Recent Economic Development of Latvia” teached by Professor Biruta Sloka at University of Latvia in Spring 2022

Download this contribution in PDF format here

Table of Content

II. Economic and Structural Policy of the EU

III. Integration of Latvia in the EU

- Methodology

- Establishment of a market economy (1991-1995)

- Candidate of EU-accession (1995-2004)

- Accession and Welfare (2004-2008)

- Crisis and Policy Adjustments (2008-2012)

- Stabilisation and Adoption of the Euro currency (2012-2019)

- Covid-19 and Outlook (2020-2022)

- Overview (1990-2022)

- Regional similarities: the case of the Baltic States

- Czech Republic: Support of the population

- Ukraine: The Role of Timing and Internal Challenges

Table of Figures

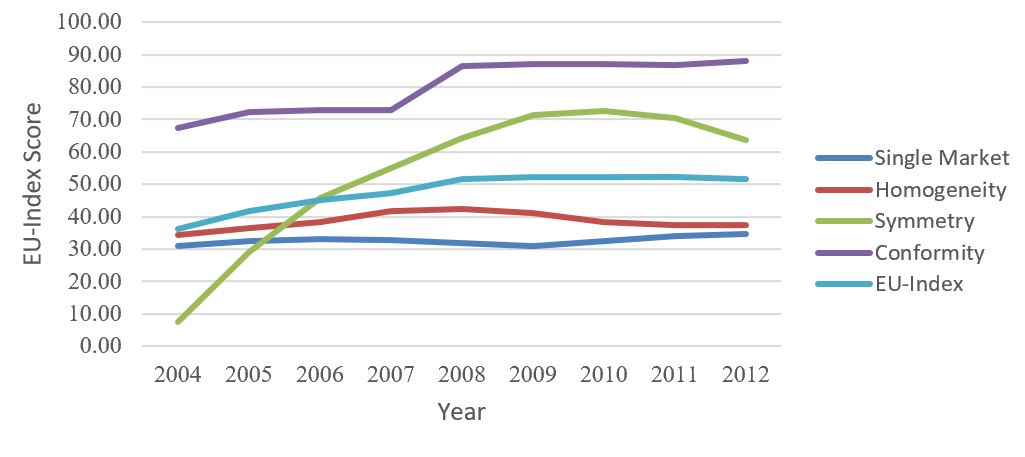

Figure 1: EU-Index of Latvia from 2004 to 2012

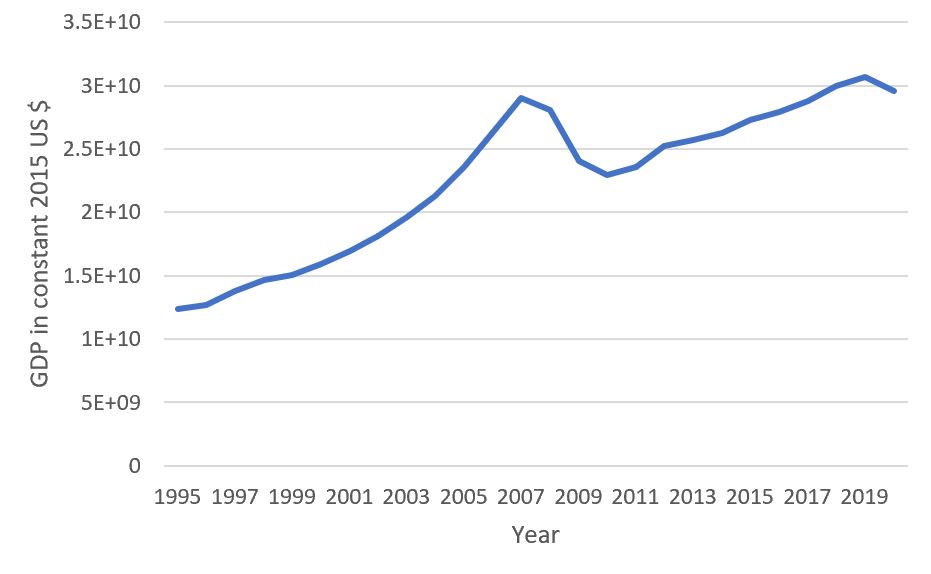

Figure 2: Latvian GDP between 1995 and 2020

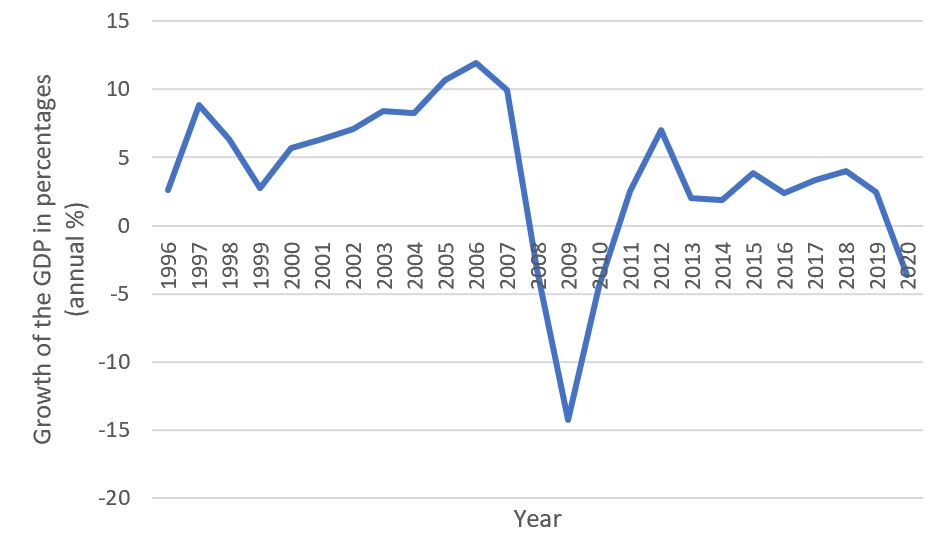

Figure 3: Growth of the GDP between 1996 and 2020

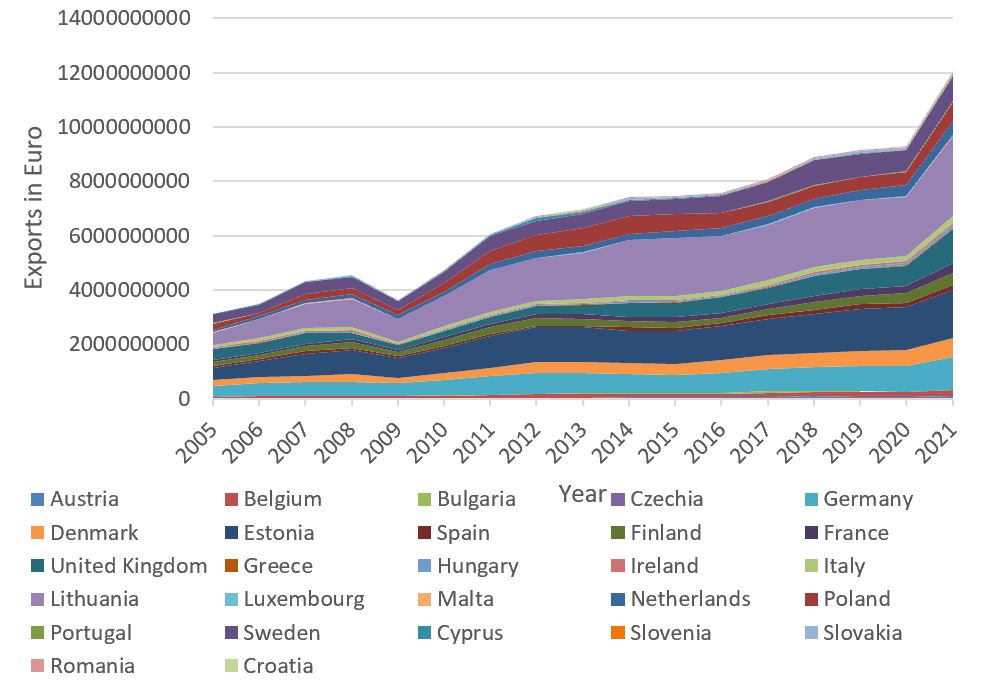

Figure 4: Exports towards EU between 2005 and 2021

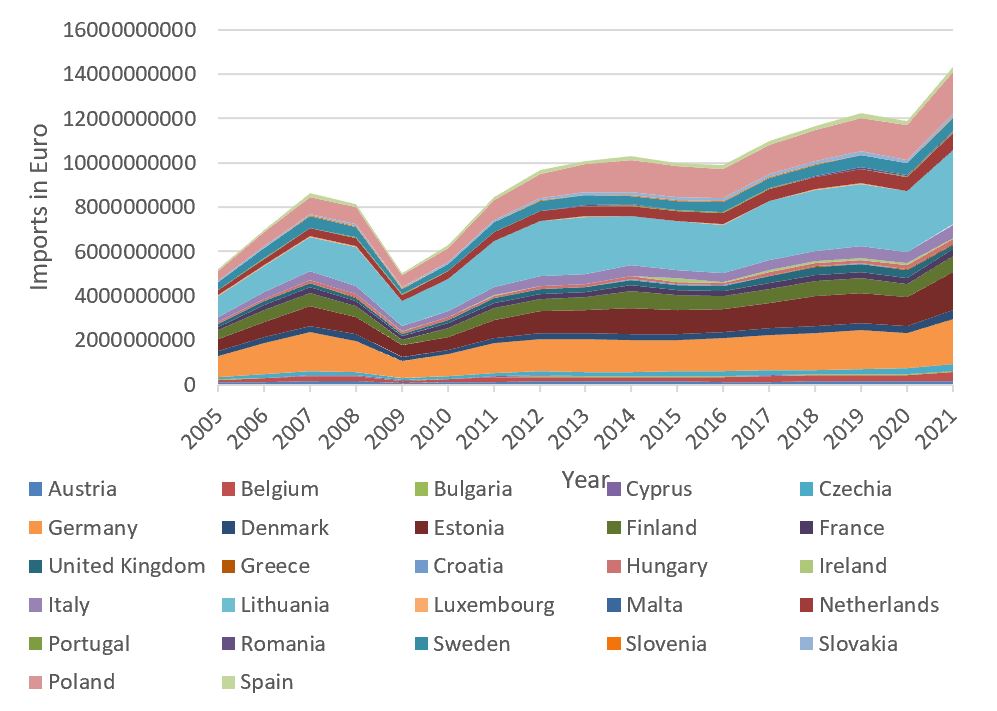

Figure 5: Exports from EU between 2005 and 2021

I. Introduction

In the past 30 years Latvia has undergone profound changes in its economy. Especially, the accession and integration in the EU has played a major role in this process by promoting economical standards as well as ideals of democracy and rule of law. Thereby, Latvia had to adapt to reach the benchmarks. Thus, integration in the EU framework is key to understand the general pattern of Latvia’s recent economic development. Other international organisations such as the OECD, NATO and WTO surely also played a role in Latvia’s development. Nonetheless, these aspects would go beyond the scope of present work and are neglected in consequence.

Therefore, present work aims to outline the integration of Latvia in the economic and structural policy of the EU from the independence 1991 until today. To do so, a macroeconomic perspective will be taken and microeconomic as well as regional aspects will be neglected. This choice has been made for a better focus on the general evolution. Nevertheless, present work is in essence multidisciplinary linking economics, trade, European law, politics, and diplomacy. The structure of the report shall help build the understanding of the reader. First, the terms and concepts will be defined. Then, the chronological evolution will be described and compared to the evolution in Estonia, Lithuania, the Czech Republic, and Ukraine. Lastly, the impact of the EU-membership on Latvia will be discussed.

II. Economic and Structural Policy of the EU

As described above, this work focuses on the economic evolution of Latvia. Therefore, the economic and structural policy of the EU is understood as the totality of opportunities and constraints given by EU to Latvia in the economic field. “Economic” includes inter alia international trade, participation in international organisation, monetary and fiscal policy, enforcement of standards in industry. “Structural” comprehends institutional as well as sectoral topics but neglects regional aspects within Latvia here. This section is dedicated to the definition of basic concepts in the field: the accession criteria more specifically norms on monetary and fiscal policy.

1. General EU-Accession Criteria

To access EU, all states must comply with the Copenhagen criteria as well as the Acquis Communautaire. For Balkan states there are nowadays additional individual requirements, but this was not the case for Latvia in the early 2000s.

The Copenhagen criteria from 1993 include political stability guaranteeing a democratic functioning of the state as well as economic, administrative, and institutional criteria1. They are broadly defined and aim to ensure basic common values such as democracy, the rule of law, free trade and human rights between member states. (European Central Bank, 2002, P. 205)[1]

The Acquis Communautaire designate the state of the integration process that has already been realised by member states and are fixed in the two fundamental European treaties TEU and TFEU1. Thereby, each Acquis is represented by one chapter and implies inter alia the establishment of a market economy if this was not the case before1. Accession candidates must comply with them to guarantee a certain homogeneity between practices in different member states. Further states are required to implement statistical systems. (European Central Bank, 2002, P. 109)1

2. Euro Adoption Criteria

To adopt the Euro, states must satisfy the Maastricht criteria from 1991, also known as convergence criteria, focus on the economic stability and rapprochement between member states2. The main topic are price stability, sound and sustainable public finances, durability of convergence and exchange rate stability. Present work considers the euro as a vital part of the EU and therefore will address the topic. (European Commission, n.d.)[2]

3. Monetary and Fiscal Policy

Specific monetary and fiscal requirements exist concerning inflation, monetary convergence, exchange rate policy, capital account, financial sector and fiscal policy (European Central Bank, 2002, P. 109)[3]. In summary, each state shall have a stable and resilient economy before becoming EU-members. In the meantime, in response to the Euro crisis 2008 different new agreements such as the fiscal compact arose which applies to the households of member states by limiting their ability to take on debt and therefore, their expenditures (Calliess, 2012)[4].

III. Integration of Latvia in the EU

1. Methodology

In present work, integration is widely defined as any actions leading to closer cooperation within the EU. The differences in argumentation between the schools of thought neofunctionalism and intergovernmentalism will be neglected to the benefit of the analysis of the outcome; Nonetheless, in the wider debate these aspects are not anodyne and can help better understanding the evolution (cf. Moga, 2009)[5].

König and Ohr (2013)[6] developed an index to measure EU-integration named EU-index. They used the differentiation between positive and negative integration. Positive integration is the allocation of governmental competences to supranational organisations and negative integration refers to the removal of trade barriers (P. 1076)6. Thereby, the observed categories were EU single market, EU homogeneity, EU symmetry and EU conformity (P. 1077)6. All these categories aimed to support trade and create a stable economy based on the view that an optimal monetary union needs complete factor mobility as well as symmetrical shocks. Present work conforms to the integrative view of the EU-index as far as the data allows it. Therefore, multiple indicators will be considered. The challenge of data availability before 2004 will be bridged with a qualitative assessment of reports and scientific works. In addition to the EU-index, the evolution of the GDP as well as exports and imports will be used as indicators for overall economical welfare and economic relations with EU.

The analysed periods were chosen to summarise the big steps in the integration process. They are following: 1991-1995, 1995-2004, 2004-2008, 2008-2012, 2012-2019 and 2020 until today.

2. Establishment of a market economy (1991-1995)

After gaining independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, Latvia replaced its formerly planned economy by a market economy. The first currency was the Latvian Rouble replaced by the Lats later. The economy was focused on heavy industry during the Soviet era and regional development was neglected. The collapse of trade relations, privatisation as well as the shock therapy resulting from the sudden changes in currency and prices led to a challenging economic situation (Reardon, 1996, P. 631)7. In consequence of the privatisation, Latvia’s unemployment rate rose significantly even if foreign investments created some jobs in the tertiary sector (Reardon, 1996, P. 633)7. The shock therapy and general insecurity implied a high inflation rate and fiscal evasion due to high taxes impeded social measures (Reardon, 1996, P. 634)7. Left- and right-wing populist parties profited from this difficult situation and massively gained support of voters during elections (Reardon, 1996, P. 634-635)[7].

Data of this time exists only sparingly and in uncertain quality. Nonetheless, the economic and political evolution of the early 1990s is key to understand later economic policies of Latvia in its EU-accession and -integration process.

3. Candidate of EU-accession (1995-2004)

Latvia expressed its intention to access European Union in 1995. The process of becoming a candidate to EU accession was perceived in different ways from the EU, the Latvian government and society. Starting 1995 data concerning Latvia’s GDP is available (cf. Figure 2 & Figure 3): the growth of the GDP is positive between 1995 and 2004 even if it slightly declined between 1997 and 1999. Overall, Latvia’s economy was promising considering the fact that it became a market economy only a few years ago.

The organs of the EU were enthusiastic concerning the plans of Latvia to join them8. In 1997 the Commission expressed its opinion about Latvia8. Politically the judicial system, minorities rights and fight against corruption needed to improve8. Economically impressive progress has been made but the GDP was still very low compared to the EU average and incomplete privatisation led to welfare losses due to not optimally used resources8. Lastly, judicial standards concerning intellectual property, taxation, data protection, public procurement and competition law lacked precision8. Overall, the Commission welcomed the EU-accession initiative but advised Latvia to join EU at a later point in time giving it the time to meet the requirements8. The European Parliament shared the view of the Commission concerning the efforts and progress of Latvia and opened the door for the possibility of accession negotiations in 1997 for the time when the requirements would be fulfilled8. In 1999 the Commission continued criticising certain of the named topics above8. The judicial system and laws as well as corruption and minority rights were still ongoing projects8. The economy consolidated remarkably, and the focus shall be on stabilisation in the early 2000s8. In December 1999 the European Council finally decided to begin with accession negotiation in February 2000 (European Parliament, 2000)[8].

The Latvian society and political landscape were divided between the right and the left wing. The right-wing parties promoted nationalist values and neoliberal economic approaches whereas the left-wing parties supported the Russian-speaking minority9. Therefore, Latvia’s economic policy debate were closely linked to ethnic questions9. For the EU, minority protection was a key aspect in social policy to become an EU-member9. The organs of the EU rather supported the left-wing parties which led to a stronger support among the Russian-speaking population for EU than among the Latvian-speaking population9. The lack of perceived improvement of the situation by the Russian-speaking persons let this support quickly fade9. In general, the support of the Latvian society was not undisputed and different pro-EU information campaigns from governmental institutions preceded the vote9. In the referendum about EU-accession in December 2002, 66.97% voted yes, 32.26% no and 0.77% votes were invalid (Eihmanis, 2019, P. 2-5; Centrālā vēlēšanu komisija, 2002)[9].

Latvia was not alone with its challenges to reach the negotiations for EU-accession: most Eastern-European countries experienced major difficulties to comply with the social and environmental policies imposed by the Aquis Communautaire (The Economist, 1994)[10]. Altogether, fulfilling the general EU requirements while balancing domestic issues was a difficult task. Thus, it is surprising that no official declaration from governmental side could be found easily during the research for present work[11].

In summary, meeting the accession requirements and EU-policies were a major challenge for the Latvian government and society. The overcoming of differences between EU-policies and domestic debates was an important step in the integration process.

4. Accession and Welfare (2004-2008)

Latvia joined the EU in 2004 and pegged its currency, the Lats, to the Euro in 2005 in a one percent band (Eihmanis, 2019, P. 8)9. This evolution shows that bond between Latvia and the EU had grown stronger. Further, Latvia had substantially changed national institutional structures and managed to stabilise its economy to meet the accession requirements (Eihmanis, 2019, P. 6-7)9. The first years of Latvia within the EU were marked by a flourishing economy and new possibilities. This can be seen in the strong growth of the GDP (cf. Figure 2 & 3) as well as in the rising of trade between Latvia and other EU-members (cf. Figure 4 & 5). Especially, the great expansion of imports from EU indicates that the relationship between Latvia and EU has improved further (cf. Figure 4).

For domestic politics, joining the EU also meant substantial financial support. Eihmanis formulated it in the following was: “EU’s political influence on Latvia became less direct, relatively shifting from import of rules to import of capital” (2019, P. 8)9. This allowed Latvia to further develop its market economy and implement several development projects. The biggest funding comes from the projects European Regional Development Fund, European Social Fund and Cohesion Fund (Eiropas Savienības fondu līdzfinansējuma saņemšana, 2020)[12]. In turns, this also meant that EU could take influence on which projects, areas and domains were supported.

Starting 2004, the EU-index (König & Ohr, 2013 & König & Ohr, n.d. & cf. Figure 1)[13] can be used as an indicator for EU-integration. From 2004 to 2008. This index takes up multiple indicators available in official data bases and creates a point system to rate four categories of EU-integration. Latvia’s conformity to EU-policies was the highest rated aspect; considering the accession criteria, this is not a big surprise. Latvia’s EU-homogeneity concerning the law of one price was slightly rising until 2008. This documents an close connexion between domestic and EU-economies. The integration in the single market was improved which can be seen more in detail in the imports and exports between Latvia and the EU in the same period. Lastly, the symmetry of the Latvian economy meaning the synchronisation of business cycles accelerated considerably. The overall EU-index made up from these four aspects therefore raised from 36.2 in 2004 to 51.55 in 2008 and show an ongoing embedding of Latvia in the institutional and economic frame of the EU.

Figure 1: EU-Index of Latvia from 2004 to 2012 (data from König & Ohr, n.d.)[14]

The first years within EU were highly profitable for Latvia and created a constructive environment for its economy to flourish. Further, the ongoing integration promoted the regional development of Latvia within the EU.

5. Crisis and Policy Adjustments (2008-2012)

In 2008 the Euro crisis hit Europe and the World. This led to a deep recession of the Latvian economy, where the lowest point was reached in 2009 with almost -15% growth of the GDP (cf. Figure 3). During the same time, exports and imports towards EU decreased and reached approximately the same level than in 2004 at the lowest point in 2008 (cf. Figure 4 & 5). This represents a higher percentage of the GDP than in 2004. The EU index indicates a slight disintegration in the single market and homogeneity, but the overall index only slightly decreased between 2008 and 2012. Further, Latvia was integrated in the Balance of Payments and the country specific recommendations of the European Semester in consequence of the default in 2008 (Ministry of Economics of the Republic Latvia, 2020)[15]. In addition, the cohesion policy fund allocated 4.6 billion euros to Latvia for the period between 2007 and 2013 (European Commission, 2014)[16]. In other terms, Latvia obtained help in crisis time from the EU and was integrated in economic crisis policy.

The Latvian government implemented severe austerity politics. Since the currency has been pegged to the SDR and starting 2005 to the euro (Eihmanis, 2019, P. 8)[17], monetary policy was impossible, and the only remaining lever was fiscal policy. Consequently, the Latvian government had to increase its revenues or to decrease its expenditures. Cutting public spending and taxing property instead of rising income taxes proved to be more tolerable by the population (Skribane & Jekabsone, 2013, P. 32)[18]. Further, it allowed the Latvian institutional organisation to be revised and optimised leading to more transparency (Cepilovs & Török, 2019, P. 1295)[19]. Therefore, it might be considered as an indirect step towards EU-integration on structural policies which would explain the ongoing integration process indicated by the EU-index. The consolidation of the Latvian economy was rapid, which can to some degree suggest a successful crisis policy. The acceptance of the measures under a cultural aspect was widely studied in literature; it points out that Latvia never had a strong welfare state and that accepting punctual measures to regain normality soon seemed bearable for a people forged by hardships in the past (cf. Cepilovs & Török, 2019, P. 1299-1300; Ozoliņa, 2019)[20] & [21]. Later the EU implemented the fiscal compact to limit the state debt to 3% per year and 60% in general; this further restricted the fiscal policy lever of national politics (Calliess, 2012)[22].

Latvia was accused of EU policy cherry picking: on the contrary to other EU members, the austerity politic was harsher then demanded and the Commission became an actor supporting social aspects (Eihmanis, 2018, P. P. 242-243)[23]. The government wanted, for example, to postpone a project concerning a guaranteed minimum income arguing that people would become lazy and stop working. The Commission then asked for evidence for those assumptions which eventually resulted in a policy change.

Older challenges such as the low share in industry, high state deficit, instability in the financial sector, unbalanced development, structural unemployment, and a suboptimal business environment remained (Skribane & Jekabsone, 2013, P. 35-36)[24]. This led to less innovation and thus to unsustainable competitiveness. Overall Latvia had a harsh time between 2008 and 2012. It managed to overcome these difficulties implementing a severe austerity politic, which went beyond the EU requirements.

6. Stabilisation and Adoption of the Euro currency (2012-2019)

In personal communication with one of the authors, it emerged that the EU-index stopped in 2012 due to personal reasons of the authors. Therefore, we cannot use this tool to analyse the integration of Latvia in the economic and structural EU-policy after this date. Nevertheless, the integrative approach will continue to be used. As explained above Latvia managed to stabilise its economy relatively quickly. From 2012 to 2019 the GDP was constantly rising and imports and exports with other EU substantially augmented.

The EU Convergence Report concerning EU members who are not part of the Euro Zone is made by the European Central Bank for the Commission. In 2013, a special report for Latvia was issued (European Commission, 2014b, P. 5-9)[25] where Latvia was considered as the best performer concerning economic EU-integration in the domains legal compatibility, price stability, public finances, exchange rate stability and long-term interests. Further, the international monetary fund came to a similar conclusion (International Monetary Fund, 2012)[26]. These assessments documented once again that Latvia had got through the Euro crisis. Therefore, the international community perceived Latvia as an economically and politically stable country.

The cohesion policy fund issued around 4.51 billion euros for economic, sustainable, social, educational, and territorial development (European Commission, 2014; Ministry of Finance of the Republic Latvia, 2020)[27]. By doing so, the EU indirectly promoted the development of its own social and structural policy. This allowed several domestic projects. Thereby, Latvia’s structural policy integration concerning social, regional, and environmental concerns was promoted. The Latvian foreign ministry pointed out the international economic and security policy as key aspects (Ārlietu ministrija, 2018)[28].

Between 2012 and 2019 the Latvian economy consolidated and further integrated itself in the EU economic and structural policy frame. This was due on one side to the actions of the government and on the other side to incentives set by the EU. The presidency of the European Council of Latvia in 2015 focused on digitalisation and can be seen as an indicator of integration (Ārlietu ministrija, 2021)[29].

7. Covid-19 and Outlook (2020-2022)

In 2020 the covid-19 pandemic hit the World by impairing business activities and interrupting supply chains. This also had effect on the Latvian economy which saw a sharp decline and even recession of its GDP in 2020 (cf. Figure 2 & 3). This nonetheless does not mean that they were less trade relations with EU. On the contrary, exports and imports continued to rise (cf. Figure 4 & 5), maybe due to the unavailability of EU-external business partners. Therefore, despite the crisis, Latvia could tighten its relationship with other EU members. Further, the recovery had been quicker than expected according to the Bank of Latvia even though the euro currently has a high inflation rate (Bank of Latvia, 2021, P. 36-37)[30]. This assessment is not unanimous, and the Ministry of Economics stated “In 2020, we implemented measures to stabilise the financial situation for citizens and entrepreneurs, but in the next two years we are taking measures to redirect the economy, […] focusing on structural economic change by purposefully adapting state aid mechanisms. From 2023 – in the growth phase – measures are provided to transform the national economy” (Ministry of Economics, 2021, P. 3)[31]. In other terms, Latvia is again using the crisis to work on structural issues. In the same manner as in 2008 with the public service sector, it here tries to reorient its sectoral structure towards a more innovation and sustainability orientated frame. This will allow Latvia to grow even further into the economic and structural EU-policy in the future.

8. Overview (1990-2022)

In this section, all information concerning the whole period 1990 to 2022 are gathered.

Figure 2: Latvian GDP between 1995 and 2020 (data from Worldbank, 2020)[32]

Figure 3: Growth of the GDP between 1996 and 2020 (data from Worldbank, 2020b)[33]

Figure 4: Exports towards EU between 2005 and 2021 (data from Central Statistics Bureau of Latvia, 2022)[34]

Figure 5: Exports from EU between 2005 and 2021(data from Central Statistics Bureau of Latvia, 2022)33

IV. Comparative Perspective

This part aims to compare the Latvian integration in the economic and structural policy of the EU with the process of other states. Firstly, the economy of the Baltic Region will shortly be described. Then, the cases of Czech Republic and Ukraine are analysed and aspects explaining their different EU-integration pattern are described. In general, it can be understood as a reflection and outlook rather than a extensive analysis. To do so, further research would be needed in future.

1. Regional similarities: the case of the Baltic States

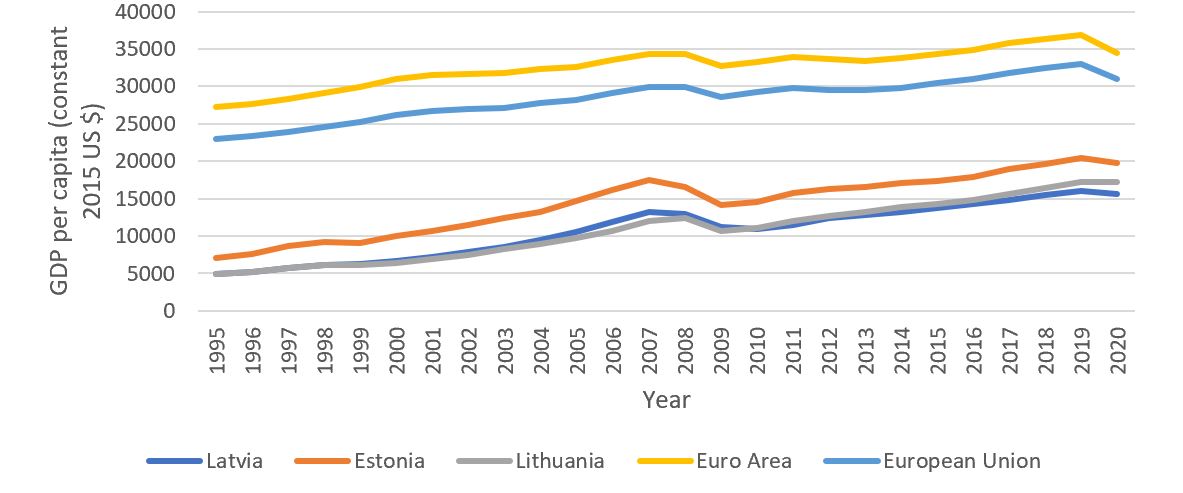

The Baltic states share many economic similarities (cf. Poissonnier, 2017)[35]. Figure 6 shows that the business cycles among the Baltic states are highly synchronised and that Latvia and Lithuania have approximately the same productivity in terms of GDP per capita. The Baltic states all have a GDP per capita which is far under the EU and Euro Area average. This difference nonetheless shrinks, because the growth is higher in the Baltic states than in the EU and Euro Area average. Further, the level of imports and exports between those three countries makes up a high percentage of the total net exports of Latvia (cf. Figure 4 & 5). The Latvian, Estonian, and Lithuanian economies are therefore more integrated together than in the EU-economy. This is not opposed to EU-integration but allows to consider them as Baltic Region in this part.

Figure 6:GDP per capita in Latvia, Estonia, Lithuania, the Euro Area, and the EU from 1995 to 2020 (data from Worldbank, 2020c)[36]

2. Czech Republic: Support of the population

Eurobarometer is a programme of the EU destined to carry out public opinion polls. To estimate the importance of the public opinion in two of the most important steps in EU-integration, accession and adoption of the Euro, an analysis of the relevant studies will be made.

Concerning the EU accession of the Baltics a study has been made in 2003. Thereby, citizens of the EU15 countries were interviewed per telephone. Only 3% estimated that the EU was very well prepared to welcome the enlargement, 36% answered “well prepared”, 44% “not well prepared”, 10% “not prepared at all” and 8% did not respond. In summary, of the effective responder 42% were rather positive and 58% were less optimistic. Interestingly, there were no further polls later about the accession of new member states. This might be due to the rather discouraging results in 2003, which would make it difficult to justify further enlargement policies. This would mean that the public opinion of citizens living in the EU concerning the accession of new memberstates is not a relevant factor in the integration processes of new states and cannot be compared to younger memberstates. (Eos Gallup Europe, 2003, P. 28)[37]

The Euro accession was more widely studied. In 2005 and 2006 respectively one study was carried out in the Latvian population asking for opinions about the adoption of the Euro; between 2004 and 2007 the level of support for the Euro sank (The Gallup Organization Hungary/Europe, 2006, P. 36; The Gallup Organization Hungary/Europe, 2007, P. 35)[38]. Later, in 2012 and 2013 these opinions remained slightly more negative than positive with respectively 53% and 55% respondents answering being against the adoption of the Euro currency (TNS Political & Social, 2013, P. 65)[39]. In the same study in Czech Republic 81% declared themselves against the introduction of the Euro in 2012 and 80% in 2013. In practice, the Euro has not been introduced in the Czech Republic. Therefore, a very strong public opinion seems to have effect on the adoption of the single currency and, in the larger sense, on the integration process. It nonetheless remains unclear if this effect is happening on the national or European level since the political discourse and economic policy in the Czech Republic avoids the adoption of the euro (cf. Pechova, 2012)[40]. The national level seems more likely since there are more democratic mechanisms than in the EU.

The support of the EU-integration among the population plays a role in the EU-integration process to the extent that it influences national politics and policies. This induces that populism and euro scepticism in national governments can be a major threat for EU-structures and the overall integration process.

3. Ukraine: The Role of Timing and Internal Challenges

Energy and food supply is a major geopolitical point for the EU. Eastern Europe plays an important role in this field since it is relatively labour abundant and endowed with important natural resources and pipelines compared to Western Europe. Ukraine therefore would be an interesting partner for the EU.

In fact, there was an association agreement between the EU and Ukraine in 2014, which was finally declined by the former Ukrainian president. The preamble of this agreement nevertheless did not contain explicit references to the possible later candidate status or accession to EU because of the objection of several EU-members; especially the internal political difficulties such as the non-compliance with the principles of democracy, the rule of law and human and minority rights were determining for this choice (Spiliopoulos, 2014, P. 259)40. In the case of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia, such economic association agreements were the first step towards a deeper EU-integration despite similar issues (Spiliopoulos, 2014, P. 256)40. The EU was itself not ready for a further enlargement in 2014, “especially to a large (in terms of area and population), and strategically positioned (particularly in the international energy map) country” (Spiliopoulos, 2014, P. 259)[41]. Further, as the authoritarian trends gained traction, the EU became increasingly disinterested which might have led to a vicious circle (Kubicek, 2005, P. 269)[42].

In summary, Ukraine was unable to access to the institutional EU-structure because it was unable to keep up with the requirements concerning democracy and domestic politics. Simultaneously, the EU was not capable to assist Ukraine in this process as it was done for Latvia earlier because of its own difficulties and the larger size of Ukraine and the wider implication of its possible accession. In the last days and in the context of the recent Russian violation of Ukraine’s territorial integrity, claims to integrate Ukraine in the EU by granting it the candidate status rose again (“It is time to officially recognize Ukraine as a candidate state to the European Union”, 2022)[43].

V. Reflexion and Discussion

Present work is subject to different limitations. Firstly, exhaustive data is only available since 2004 which makes it hard to compare and identify integration trends. Further, since the EU index was only carried out until 2012, an important analysis tool is missing, and the scope of present work does not allow an as extensive analysis as it was done for the earlier period. Lastly, the lack of Latvian skills of the author hampers the ability to identify necessary information. Thus, the report was made as good as it was possible in given conditions.

In the larger debate one could ask whether EU was profitable for Latvia. Scholars are not unanimous on that topic: some argument that it is impossible to know which effect EU had on Latvia (Andersen, Barslund, & Vanhuysse, 2019)[44] whereas other claims that EU-membership induced high welfare gains (Campos, Coricelli & Moretti 2019)[45]. Present work cannot confirm or deny either of those statements.

VI. Conclusion

Present work aimed to outline the Latvian integration in the economic and structural policy frame of the EU. It demonstrated the difficult pattern to accede first candidate and later member status obliging Latvia not only to stabilise its economy but also to comply with numerous political and democratic standards. Finding a balance between national politics and EU requirements in these times was a major challenge. The first years within the EU were characterised by strong economic growth and the strengthening of trade relations with other EU members. The financial crisis obliged Latvia to restructure its public service because the only remaining lever was fiscal policy. From 2012 until today various projects aiming to support regional development and cohesion within the EU are carried out. The covid-19 crisis is seen as an opportunity for Latvia to restructure its economic sector towards a more sustainable pattern of competitiveness. The EU further also support Latvia’s recovery by financial means. Thus, EU-integration is an ongoing process in Latvia. Big steps have been made in the past but there is no point where integration is accomplished. In the wider debate, it is even discussed whether further integration is beneficial to the EU or not. Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia are more integrated together in the Baltic Region than in the EU. Therefore, the importance of regional trade structures is highlighted and the vision of the EU as a unique block is eased. By comparing Latvia to the Czech Republic and Ukraine, the complexity of integration processes was demonstrated by identifying several aspects which can jeopardize such endeavour. In conclusion, Latvia’s integration in the economic and structural policy of the EU was successful until here and gives hope for a bright future.

Bibliography

Andersen, T.B., Barslund, M. & Vanhuysse, P. (2019). Joint to prosper? Kyklos, 72(2), forthcoming. Retrieved from: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2791958

Ārlietu ministrija. (2018). Annual Report of the Minister of Foreign Affairs on the accomplishments and further work with respect to national foreign policy and the European Union 2018. Ārlietu ministrija. Retrieved from https://www.mfa.gov.lv/en/media/2223/download

Bank of Latvia. (2021). Macroeconomics Developments Report: September 2021 (Report No 33). Bank of Latvia.

Calliess, C. (2012). From Fiscal Compact to Fiscal Union? New Rules for the Eurozone. Cambridge Yearbook of European Legal Studies, 14, P. 101-117. doi:10.5235/152888712805580345

Campos, N.F., Coricelli, F. & Moretti, L. (2019). Institutional integration and economic growth in Europe. Journal of Monetary Economics, 104, P. 88-104. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2018.08.001

Central Statistics Bureau of Latvia. (2022). Exports and imports by countries (CN at 8-digit level) 2005M01 – 2021M12 [dataset]. Central Statistics Bureau of Latvia. Retrieved from: https://data.stat.gov.lv/pxweb/en/OSP_PUB/START__TIR__AT__ATD/ATD080m

Centrālā vēlēšanu komisija. (2002). Results of National Referendum on Latvia’s Membership in the EU. Retrieved from: https://www.cvk.lv/cgi-bin/wdbcgiw/base/sae8dev.aktiv03era.vis

Cepilovs, A., & Török, Z. (2019). The politics of fiscal consolidation and reform under external constraints in the European periphery: comparative study of Hungary and Latvia. Public management review, 21(9), 1287-1306. doi:10.1080/14719037.2019.1618384

Eihmanis, E. (2018). Cherry-picking external constraints: Latvia and EU economic governance, 2008-2014. Journal of European public policy, 25(2), 231-249. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1363267

Eihmanis, E. (2019). Latvia and the European Union. Oxford Research Encyclopedias. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.1039

Eiropas Savienības fondu līdzfinansējuma saņemšana. (2020). EU funds: General information. Ministry of Finance of Latvia. Retrieved on the 25th of February 2022 from https://www.esfondi.lv/general-nformation-1

Eos Gallup Europe. (2003). Enlargement of the European Union [Flash Eurobarometer 140]. European Commission Directorate General “Press and Communication”. Retrieved from: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/299

European Central Bank. (2002). Annual Report 2001. European Central Bank. Retrieved from https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/annrep/ar2001en.pdf?2757822b4e033da33c8d92e5d4d75e14

European Commission. (2014a). Cohesion Policy and Latvia. European Commission. Retrieved from: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/information/cohesion-policy-achievement-and-future- investment/factsheet/latvia_en.pdf

European Commission. (2014b). Convergence Report 2013 on Latvia (European Economy N° 3/2013). European Union. Retrieved from: https://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/european_economy/2013/pdf /ee3_en.pdf European Commission. (n.d.). Convergence criteria for joining. European Commission Website. Retrieved on the 25th of February 2022 from https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/euro-area/enlargement-euro- area/convergence-criteria-joining_en

European Parliament. (2000). Latvia and the Enlargement of the European Union (Briefing No 10). European Parliament. Retrieved from https://www.europarl.europa.eu/enlargement/briefings/10a3_en.htm

“It is time to officially recognize Ukraine as a candidate state to the European Union” (24th of February 2022). Le Monde. Retrieved from: https://www.lemonde.fr/le-monde-in-english/article/2022/02/24/it-is-time–to-officially-recognize-ukraine-as-a-candidate-state-to-the-european-union_6115127_5026681.html

König, J. & Ohr, R. (n.d.) EU-Index: Messung ökonomischer Integration in der Europäischen Union. EU-Index. Retrieved on the 25th of February 2022 from http://www.eu-index.uni-goettingen.de/?lang=de

König, J., & Ohr, R. (2013). Different Efforts in European Economic Integration: Implications of the EU Index. Journal of common market studies, 51(6), 1074-1090. doi:10.1111/jcms.12058

Kubicek, P. (2005). The European Union and democratization in Ukraine [UKRAINE: ELECTIONS AND DEMOCRATISATION]. Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 38(2). P. 269-292. Retrieved from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/48609540

Ministry of Economics of the Republic Latvia. (2020). European Semester. Ministry of Economics of the Republic Latvia. Retrieved from https://www.em.gov.lv/en/european-semester

Ministry of Economics. (2021). Economic Development of Latvia. Ministry of Economics. Retrieved from: https://www.em.gov.lv/en/media/13388/download

Ministry of Finance of the Republic Latvia. (2020). EU Funds. Ministry of Finance of the Republic Latvia. Retrieved on the 25th of February 2022 from https://www.fm.gov.lv/en/eu-funds

Moga, T.L. (2009). The Contribution of the Neofunctionalist and Intergovernmentalist Theories to the Evolution of the European Integration Process. Journal of Alternative Perspectives in the Social Sciences, 1(3), P. 796-807. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/40542728_The_Contribution_of_the_ Neofunctionalist_and_Intergovernmentalist_Theories_to_the_Evolution_of_the_European_Integration_Process

Ozoliņa, L. (2019). Embracing austerity? An ethnographic perspective on the Latvian public’s acceptance of austerity politics. Journal of Baltic studies, 50(4), 515-531. doi:10.1080/01629778.2019.1635174

Pechova, A. (2012). Legitimising discourses in the framework of European integration: The politics of Euro adoption in the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Review of International Political Economy, 19(5). P. 779-807. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2011.633477

Reardon, J. (1996). An Assessment of the Transition to a Market Economy in the Baltic Republics. Journal of economic issues, 30(2), 629-638. doi:10.1080/00213624.1996.11505827

Poissonnier, A. (2017). The Baltics: Three Countries, One Economy? [European Economy Economic Briefs 024]. European Commission. Retrieved from: https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/economy-finance/baltics-three-countries-one-economy_en

Skribane, I., & Jekabsone, S. (2013). Structural Changes in the Economy of Latvia After it Joined the European Union. Intelektine ekonomika, 7(1).

Spiliopoulos, O. (2014). The EU-Ukraine Association Agreement As A Framework Of Integration Between The Two Parties [The Economies of Balkan and Eastern Europe Countries in the Changed World (EBEEC 2013)]. Procedia Economics and Finance, 9, P. 256 – 263. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(14)00027-6

The Gallup Organization Hungary/Europe. (2006). Introduction of the Euro in the New Member States [Analytical Report 1244 / 191]. European Commission Directorate-General “Economic and Financial Affairs”. Retrieved from: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/1244

The Gallup Organization Hungary/Europe. (2007). Introduction of the Euro in the New Member States [Analytical Report 642 / 207]. European Commission Directorate-General “Economic and Financial Affairs”. Retrieved from: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/642

The Economist. (10th of December 1994). Eastern Europe and the EU: Laying down the law. The Economist. Retrieved on the 25th of February from: https://www.proquest.com/docview/224132950?accountid=28962&forcedol=true

TNS Political & Social. (2013). Introduction of the euro in the more recently acceded Member States [Flash Eurobarometer 1074 / 377]. European Commission Directorate-General “Economic and Financial Affairs”. Retrieved from: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/1074

Worldbank. (2020a). GDP (constant 2015 US$) [dataset]. Retrieved from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD

Worldbank. (2020b). GDP growth (annual %) – Latvia [dataset]. Retrieved from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?end=2020&locations=LV&start =1996&view=chart

Worldbank. (2020c). GDP per capita (constant 2015 US $)-Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, European Union, Euro Area [dataset]. Worldbank. Retrieved from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.KD?locations=LV-EE-LT-EU-XC

[1] European Central Bank. (2002). Annual Report 2001. European Central Bank. Retrieved from https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/annrep/ar2001en.pdf?2757822b4e033da33c8d92e5d4d75e14

[2] European Commission. (n.d.). Convergence criteria for joining. European Commission Website. Retrieved on the 25th of February 2022 from https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/euro-area/enlargement-euro-area/convergence-criteria-joining_en

[3] European Central Bank. (2002). Annual Report 2001. European Central Bank. Retrieved from https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/annrep/ar2001en.pdf?2757822b4e033da33c8d92e5d4d75e14

[4] Calliess, C. (2012). From Fiscal Compact to Fiscal Union? New Rules for the Eurozone. Cambridge Yearbook of European Legal Studies, 14, P. 101-117. doi:10.5235/152888712805580345

[5] Moga, T.L. (2009). The Contribution of the Neofunctionalist and Intergovernmentalist Theories to the Evolution of the European Integration Process. Journal of Alternative Perspectives in the Social Sciences, 1(3), P. 796-807. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/40542728_The_Contribution_of_the_ Neofunctionalist_and_Intergovernmentalist_Theories_to_the_Evolution_of_the_European_Integration_Process

[6] König, J., & Ohr, R. (2013). Different Efforts in European Economic Integration: Implications of the EU Index. Journal of common market studies, 51(6), 1074-1090. doi:10.1111/jcms.12058 & König, J. & Ohr, R. (n.d.) EU-Index: Messung ökonomischer Integration in der Europäischen Union. EU-Index. Retrieved on the 25th of February 2022 from http://www.eu-index.uni-goettingen.de/?lang=de

[7] Reardon, J. (1996). An Assessment of the Transition to a Market Economy in the Baltic Republics. Journal of economic issues, 30(2), 629-638. doi:10.1080/00213624.1996.11505827

[8] European Parliament. (2000). Latvia and the Enlargement of the European Union (Briefing No 10). European Parliament. Retrieved from https://www.europarl.europa.eu/enlargement/briefings/10a3_en.htm

[9] Eihmanis, E. (2019). Latvia and the European Union. Oxford Research Encyclopedias. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.1039 & Centrālā vēlēšanu komisija. (2002). Results of National Referendum on Latvia’s Membership in the EU. Retrieved from: https://www.cvk.lv/cgi-bin/wdbcgiw/base/sae8dev.aktiv03era.vis

[10] The Economist. (10th of December 1994). Eastern Europe and the EU: Laying down the law. The Economist. Retrieved on the 25th of February from: https://www.proquest.com/docview/224132950?accountid=28962&forcedol=true

[11] The author needs to point out its own lack of knowledge of the Latvian language; such information might exist in Latvian but could not be found in English, German, or French.

[12] Eiropas Savienības fondu līdzfinansējuma saņemšana. (2020). EU funds: General information. Ministry of Finance of Latvia. Retrieved on the 25th of February 2022 from https://www.esfondi.lv/general-information-1

[13] König, J., & Ohr, R. (2013). Different Efforts in European Economic Integration: Implications of the EU Index. Journal of common market studies, 51(6), 1074-1090. doi:10.1111/jcms.12058 & König, J. & Ohr, R. (n.d.) EU-Index: Messung ökonomischer Integration in der Europäischen Union. EU-Index. EU-Index. Retrieved on the 25th of February 2022 from http://www.eu-index.uni-goettingen.de/?lang=de

[14] König, J. & Ohr, R. (n.d.) EU-Index: Messung ökonomischer Integration in der Europäischen Union. EU-Index. Retrieved on the 25th of February 2022 from http://www.eu-index.uni-goettingen.de/?lang=de

[15] Ministry of Economics of the Republic Latvia. (2020). European Semester. Ministry of Economics of the Republic Latvia. Retrieved from https://www.em.gov.lv/en/european-semester

[16] European Commission. (2014a). Cohesion Policy and Latvia. European Commission. Retrieved from: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/information/cohesion-policy-achievement-and-future-investment/factsheet/latvia_en.pdf

[17] Eihmanis, E. (2019). Latvia and the European Union. Oxford Research Encyclopedias. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.1039

[18] Skribane, I., & Jekabsone, S. (2013). Structural Changes in the Economy of Latvia After it Joined the European Union. Intelektine ekonomika, 7(1).

[19] Cepilovs, A., & Török, Z. (2019). The politics of fiscal consolidation and reform under external constraints in the European periphery: comparative study of Hungary and Latvia. Public management review, 21(9), 1287-1306. doi:10.1080/14719037.2019.1618384

[20] Cepilovs, A., & Török, Z. (2019). The politics of fiscal consolidation and reform under external constraints in the European periphery: comparative study of Hungary and Latvia. Public management review, 21(9), 1287-1306. doi:10.1080/14719037.2019.1618384

[21] Ozoliņa, L. (2019). Embracing austerity? An ethnographic perspective on the Latvian public’s acceptance of austerity politics. Journal of Baltic studies, 50(4), 515-531. doi:10.1080/01629778.2019.1635174

[22] Calliess, C. (2012). From Fiscal Compact to Fiscal Union? New Rules for the Eurozone. Cambridge Yearbook of European Legal Studies, 14, P. 101-117. doi:10.5235/152888712805580345

[23] Eihmanis, E. (2018). Cherry-picking external constraints: Latvia and EU economic governance, 2008-2014. Journal of European public policy, 25(2), 231-249. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1363267

[24] Skribane, I., & Jekabsone, S. (2013). Structural Changes in the Economy of Latvia After it Joined the European Union. Intelektine ekonomika, 7(1).

[25] European Commission. (2014b). Convergence Report 2013 on Latvia (European Economy N° 3/2013). European Union. Retrieved from: https://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/european_economy/2013/pdf /ee3_en.pdf

[26] International Monetary Fund. (2012). Staff Country Report [Report No 12 /171]. International Monetary Fund.

[27] European Commission. (2014a). Cohesion Policy and Latvia. European Commission. Retrieved from: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/information/cohesion-policy-achievement-and-future-investment/factsheet/latvia_en.pdf & Ministry of Finance of the Republic Latvia. (2020). EU Funds. Ministry of Finance of the Republic Latvia. Retrieved on the 25th of February 2022 from https://www.fm.gov.lv/en/eu-funds

[28] Ārlietu ministrija. (2018). Annual Report of the Minister of Foreign Affairs on the accomplishments and further work with respect to national foreign policy and the European Union 2018. Ārlietu ministrija. Retrieved from https://www.mfa.gov.lv/en/media/2223/download

[29] Ārlietu ministrija. (2021). Latvia’s Presidency of the Council of the EU. Ārlietu ministrija. Retrieved on the 28th of February 2022 from: https://www.mfa.gov.lv/en/latvias-presidency-council-eu?utm_source=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com%2F

[30] Bank of Latvia. (2021). Macroeconomics Developments Report: September 2021 (Report No 33). Bank of Latvia.

[31] Ministry of Economics. (2021). Economic Development of Latvia. Ministry of Economics. Retrieved from: https://www.em.gov.lv/en/media/13388/download

[32] Worldbank. (2020a). GDP (constant 2015 US$) [dataset]. Retrieved from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD

[33] Worldbank. (2020b). GDP growth (annual %) – Latvia [dataset]. Retrieved from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?end=2020&locations=LV&start=1996&view=chart

[34] Central Statistics Bureau of Latvia. (2022). Exports and imports by countries (CN at 8-digit level) 2005M01 – 2021M12 [dataset]. Central Statistics Bureau of Latvia. Retrieved from: https://data.stat.gov.lv/pxweb/en/OSP_PUB/START__TIR__AT__ATD/ATD080m

[35] Poissonnier, A. (2017). The Baltics: Three Countries, One Economy? (European Economy Economic Briefs 024). European Commission. Retrieved from: https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/economy-finance/baltics-three-countries-one-economy_en

[36] Worldbank. (2020c). GDP per capita (constant 2015 US $)-Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, European Union, Euro Area [dataset]. Worldbank. Retrieved from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.KD?locations=LV-EE-LT-EU-XC

[37] Eos Gallup Europe. (2003). Enlargement of the European Union [Flash Eurobarometer 140]. European Commission Directorate General “Press and Communication”. Retrieved from: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/299

[38] The Gallup Organization Hungary/Europe. (2006). Introduction of the Euro in the New Member States [Analytical Report 1244 / 191]. European Commission Directorate-General “Economic and Financial Affairs”. Retrieved from: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/1244 & The Gallup Organization Hungary/Europe. (2007). Introduction of the Euro in the New Member States [Analytical Report 642 / 207]. European Commission Directorate-General “Economic and Financial Affairs”. Retrieved from: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/642

[39] TNS Political & Social. (2013). Introduction of the euro in the more recently acceded Member States [Flash Eurobarometer 1074 / 377]. European Commission Directorate-General “Economic and Financial Affairs”. Retrieved from: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/1074

[40] Pechova, A. (2012). Legitimising discourses in the framework of European integration: The politics of Euro adoption in the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Review of International Political Economy, 19(5). P. 779-807. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2011.633477

[41] Spiliopoulos, O. (2014). The EU-Ukraine Association Agreement As A Framework Of Integration Between The Two Parties [The Economies of Balkan and Eastern Europe Countries in the Changed World (EBEEC 2013)]. Procedia Economics and Finance, 9. P. 256 – 263. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(14)00027-6

[42] Kubicek, P. (2005). The European Union and democratization in Ukraine [UKRAINE: ELECTIONS AND DEMOCRATISATION]. Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 38(2). P. 269-292. Retrieved from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/48609540

[43] “It is time to officially recognize Ukraine as a candidate state to the European Union” (24th of February 2022). Le Monde. Retrieved from: https://www.lemonde.fr/le-monde-in-english/article/2022/02/24/it-is-time-to-officially-recognize-ukraine-as-a-candidate-state-to-the-european-union_6115127_5026681.html

[44] Andersen, T.B., Barslund, M. & Vanhuysse, P. (2019). Joint to prosper? Kyklos, 72(2), forthcoming. Retrieved from: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2791958

[45] Campos, N.F., Coricelli, F. & Moretti, L. (2019). Institutional integration and economic growth in Europe. Journal of Monetary Economics, 104, P. 88-104. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2018.08.001