Czech military intelligence director, Jan Beroun, suggested that the Czech Republic’s involvement and cooperation in Africa should increase.[1] Sahel, specifically is a new direction of the Czech foreign policy as the government believes that stabilisation of the region will benefit Europe as a whole.[2] Vit Rakusan, Minister of Interior during his visit to Senegal, Ghana and Rwanda highlighted the importance of European cooperation in Africa, calling for the prevention of the spreading of Chinese and Russian influence on the continent.[3] In light of recent diplomatic shifts in Franco-African relations, Europe appears to lag behind Russia and China, the two powers that aided the continent’s struggle for independence. However, the former Eastern Bloc holds a unique advantage that the EU underutilises. Unlike Russia, these nations not only supported independence struggles but also refrained from imperialist ambitions. Crucially, the democratic transitions in Central and Eastern European (CEE) EU member states offer valuable insights for African developmental efforts. The CEE nations could play a far more impactful role in EU-Africa relations if both EU institutions and established member states regarded them as full-fledged members instead of accession states. Leveraging their history of partnerships with African nations, their transition experiences, and ongoing development efforts could be effective for establishing truly equal relations with Africa.

Russia’s hold over Africa is strengthening. Unlike other major powers, Russia can’t offer much in the financial sector. Weaponising instability, Russian private military groups gain access to African resources, specifically in the Sahel.

However, Russian disinformation campaigns may prove to be a far more dangerous development for the West.[4] It is a continuation of Russian hybrid warfare, aimed at fragmenting already divided society.[5] Bryanton researched Soviet involvement in Africa, suggesting the following indicators of serious Soviet penetration of an African state:

- The presence of Soviet military bases or access to military facilities

- The presence of substantial Soviet-bloc (including Cuba) troops or military advisors (significantly more than in comparable African states)

- Extensive trade relations which make the Soviet Union a major trade partner

- Equipping the armed forces with a preponderance of Soviet-bloc military equipment

- A substantial number of students from that country studying in the USSR

- Governments that proclaim Marxist-orientalism with a special relationship with the USSR

Using Brayton’s framework, we suggest contemporary indicators of significant Russian presence per African country:

- Presence of the Russian military bases or access to military facilities (either to Russia or Russian mercenary groups)

- Substantial presence of mercenary groups and Russian military advisors

- Extensive trade relations with Russia, specifically grain reliance

- Russian nuclear presence (Rosatom)

- The preponderance of Russian military equipment

- Anti-imperial rhetoric with a pro-Russian sentiment

Bryanton highlights that during the Cold War, the USSR managed to penetrate mostly unstable African states; out of eighteen ‘fairly stable states’ according to Brayton’s categorisation, only one was exposed to significant Soviet penetration – Guinea.[6] This is a striking difference with fourteen out of twenty ‘fairly unstable states’ that fell under the Soviet influence.[7] Therefore, the more the Russian disinformation campaign succeeds in fragmenting the African states, the more influence Russia will be able to wield in the region. This underscores the importance of the European counter-disinformation campaign in Africa to illustrate Russia’s not so anti-imperial intent, or past. CEE states can both attest to this and spearhead this effort without raising suspicion or resentment from African states, as seen in French attempts. So what is Russian history in Africa?

Russian history in Africa extends back to Peter I’s unsuccessful expedition to Madagascar as he attempted to jump on the European colonial bandwagon.[8] During the Berlin Conference, the Russian Empire, as well as eight other participating states, found themselves out of the Scramble for Africa. The continent, however, aroused a growing interest among the Russian elites with the New Moscow colony appearing in modern-day Djibouti for less than a month. Ashinov, a self-proclaimed cossack, was the agitator for the private African expedition in 1888.[9] The prospect of gaining access to the Red Sea and establishing triangular trade in Africa excited the higher imperial elite and persuaded Alexander III to greenlight Achinov’s mission. [10] Under Nicholas II, certain Russian elites daydreamed about a Russian colony in the Christian Orthodox Abyssinia. However, the limited successes were curved by the losses suffered after the Russo-Japanese War.

Leontiev facilitated Ethiopian-Russian relations and assisted Ethiopians in the war against Italy. Currently, Leontiev is praised as an anti-colonial hero, however, Polianichev highlights Leontiev’s genuine ambition in Africa:

I will take all elephant tusks, I will exhaust all my future slaves, and only then will I think about the history of Abyssinia.[11]

These examples of the Russian imperial attempts at African colonialism, albeit unsuccessful and inconsequential, set the framework for Russian involvement on the continent. The existing international system and Russian economy subject Russia’s colonial expansion to its surrounding territory. The elites, aware of Africa’s riches and jealous of European powers’ success, still yearn for Russian African expansion, including influential figures, for example, Sergei Witte.[12] Thus, private missionaries, often enabled by the government, became the stencil for Russian activity in Africa. It presented a win-win scenario for the Russian government: upon success, it can claim its ownership, upon failure, akin to Ashinov’s scenario, it can deny affiliation. This framework is presently relevant in the context of Wagner missionaries and exhibits historical precedent during the Cold War era.

In 1919, the Comintern published a declaration of solidarity with “The colonial slaves of Africa and Asia. The hour of proletarian dictatorship in Europe will strike for you as the hour of your own emancipation!”[13] The rhetoric was in line with Lenin’s Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism. Both Trotsky and Lenin closely studied the Anglo-Boer, which featured twice in the first volume of Iskra.[14] Trotsky’s “Letter to South African Revolutionaries” and collaboration with C.L.R. James earned him a standing among prominent African left. However, as Matusevich demonstrates, the chief spokesman for Africa in the Comintern were white members of the South African Communist Party.[15]

At the closing stage of the Second World War, the anti-imperial Soviets asked for a mandate over Tripolitania (Libya).[16] Molotov was “instructed to raise the question,” Soviet leadership was cashing in on the vague promise made by FDR’s Secretary of State, Edward Stettinius, at the San Francisco conference in 1945.[17] The Kremlin’s hope for the mandate, or a naval base in the Mediterranean was killed in its infancy by U.S.-British and Turkish resistance.[18]

Russian imperialism in Central Asia and forced conversion to Orthodoxy mirrors Western powers’ “civilizing missions.” Russia may disguise its imperialism in the communist rhetoric or Putin’s vision of a just multipolar world but in reality, Russian contribution to Western colonialism is integral as the Great Game competition suggests.

However, Russian disinformation campaigns may prove to be a far more dangerous development for the West. It is a continuation of Russian hybrid warfare, aimed at fragmenting already divided society.[19] Bryanton researched Soviet involvement in Africa, suggesting the following indicators of serious Soviet penetration of an African state:

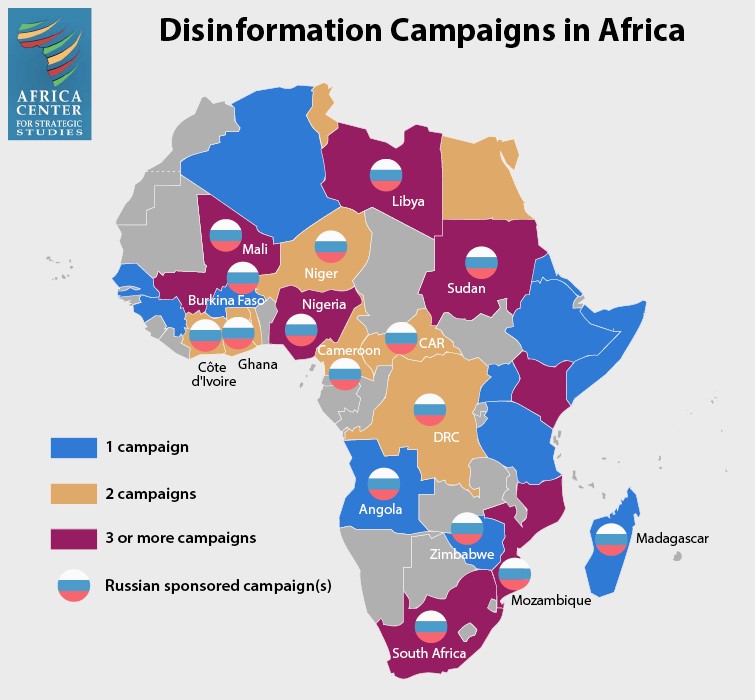

Disinformation campaigns that have been detected and publically documented. Extracted from Africa Centre for Strategic Studies at https://africacenter.org/spotlight/mapping-disinformation-in-africa

References:

Olympia de Maismont/AFP via Getty Images,Baner with Putin at the protest in Burkina Faso

[1]https://www.expats.cz/czech-news/article/czech-officials-advocate-stronger-africa-collaboration-to-address-illegal-immigration

[2]Vile Rehak, Josef Kucera, New Impulses for Czech Strategy in Africa, Hans Seidel Stiftung, p. 10. https://www.amo.cz/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/AMO_New_Impulses_for_Czech_Strategy_in_Africa_web.pdf

[3]https://www.expats.cz/czech-news/article/czech-interior-minister-africa-presents-opportunities-for-long-term-partnership

[4] Candace Rondeaux, Decoding the Wagner Group: Analysing the Role of Private Military Security Contractors in Russian Proxy Warfare, New American p. 12

[5] https://africacenter.org/spotlight/mapping-disinformation-in-africa/

[6]Abbott A. Brayton, “Soviet Involvement in Africa.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 17, no. 2 (1979), p. 263 http://www.jstor.org/stable/160717.

[7]Brayton, p. 263

[8]Макрушин А.В., Макрушин В.А. Фрегаты Петра отплывают к Индийскому океану // Сборник Бригантина, М., Издательство «Молодая гвардия», 1971, С. 290 – 293

[9]Oleksandr Polianchev, “How Russia tried to colonise Africa and failed,” Aljazeera, May 2023 https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2023/5/24/how-russia-tried-to-colonise-africa-and-failed.

[10]Oleksandr Polianchev, “How Russia tried to colonise Africa and failed,” Aljazeera, May 2023 http://az.lib.ru/k/krasnow_p_n/text_0260.shtml as cited in https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2023/5/24/how-russia-tried-to-colonise-africa-and-failed .

[11]Polianchev, “How Russia tried to colonise Africa and failed,” https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2023/5/24/how-russia-tried-to-colonise-africa-and-failed .

[12]Polianchev, “How Russia tried to colonise Africa and failed,” https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2023/5/24/how-russia-tried-to-colonise-africa-and-failed

[13]https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1924/ffyci-1/ch01.htm

[14]Irina Filatova and Apollon Davidson. “‘We, the South African Bolsheviks’: The Russian Revolution and South Africa.” Journal of Contemporary History 52, no. 4 (2017), p. 951. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26416645.

[15] Maxim Matusevich, “Revisiting the Soviet Moment in Sub-Saharan Africa” History Compass. (2009), p.1261.

[16]Zubok, Vladislav M.. Failed Empire : The Soviet Union in the Cold War from Stalin to Gorbachev, The University of North Carolina Press, 2007, p. 38

[17] Zubok, p. 38, molotov remembers; Feliks I. Chuev, Molotov Remembers: Inside Kremlin Politics (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1993), p. 74.

[18] Zubok, p. 39.

[19] https://africacenter.org/spotlight/mapping-disinformation-in-africa/

Picture: Image by pvproductions on Freepik